In Search of My Mother's Garden

Sharing a chapter of my memoir in honor of the 2nd anniversary of my mother's death

Today marks two years since my ma died, and tomorrow makes three years since the last time I saw and spoke to her. So much has happened over this time, including finding that ma left me all of her writing, including a memoir she started but never completed. This, of course, changed the book I thought I was writing. The book is still called A Dim Capacity for Wings, but now, in many ways, I am co-writing it with my mother. An excerpt titled An Epistle for Edenia was published in AGNI last year.

Today, in honor of my ma and our evolving relationship, I am publishing the second chapter of my memoir.

In Search of My Mother’s Garden by Vanessa Mártir

I was all of four years old but I remember when we moved into that first floor apartment on Palmetto Street in Bushwick, Brooklyn in the spring of 1980. The same apartment I grew up in. The apartment my mother never left. That was the year retired film actor Ronald Reagan was elected the 40th president of the US and a new music genre rose out of the Bronx onto the national stage with Sugar Hill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight. That summer a heat wave scorched the city. Ma didn’t let any of that stop her.

I watched her standing by the window one morning, surveying the backyard. The steam from the coffee in her hand fogged the glass. There were piles of trash everywhere, and the makeshift barriers that separated ours from the surrounding yards were made of plywood, clumsily nailed together and falling apart so there were gaping holes in spots. My eyes landed on the tree in the far left corner of the yard.

Days later, ma climbed out the window and went to work, sweeping up the years of garbage, bags that smelled of something dead or dying, cracked flower pots, a fork with twisted tongs; and threw it all over the dilapidated fence into the junk yard next door which was already piled high with trash. It was one of the many rubble strewn lots that dotted our neighborhood back then.

I tiptoed past her and stood at the foot of the tree; I’d learn later it was a plum tree. A past resident had painted the trunk a dull salmon color. I picked at the chipping paint, pulling some trunk with it, patted the tree and whispered, “Hi. I’m Vanessa.” I was scrawny, a wee thing really, but already unstoppable.

Decades later I overheard ma tell someone: “Vanessa was always big. Even when she was little, she was big.”

I started grappling up the trunk, scraping my legs and hands, peeling the pleather off my sneakers. At one point, a sharp branch stabbed into my side. I winced but kept climbing. Ma screamed at me to get down, “Te vas a dar un mal golpe, machúa!” But I wasn’t bothered by being called a tomboy. I saw nothing wrong with doing things girls weren’t “supposed to” do. Who made those rules anyway? She cut her eyes at me while I kept climbing. “No vengas llorando cuando te caigas, ¿oíste?!” It took me weeks, but I didn’t give up, and neither did she.

Ma wasn’t the Martha Stewart type of gardener with a sun hat and apron. She worked in a sofrito stained nightgown or a t-shirt and shorts. She found an old shovel and took to tilling the soil, using her right leg to push the shovel into the ground to bring up the dark soil and squirming earthworms. When the earth wouldn’t give, she got on all fours and used her hands. Then she went out and bought the seeds. When she laid them out on the kitchen table, I saw that each packet had a picture of the potential inside: peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, squash, herbs like peppermint, cilantro and rosemary, flowers like geraniums and sunflowers. She handled the seeds with a tenderness I envied.

I can still see her now, hands in the soil, the dirt is caked in the creases and under her fingernails. She stands, raises her face to the sun, closes her eyes, her lips curl into a toothless smile. She inhales so deep, I watch the air swell her belly and climb back out. A satisfied sigh. It’s the most content I ever saw her.

The first time I put my hands in that soil was after a storm. I sunk my hands into the black mud and brought it up to my nose. Forty five years later, I still remember the way the smell wafted into me, a smell I swore I knew and that it knew me. I sat there for a while, inhaling the smell that was somehow both familiar and foreign. How could I know this earth? We’d just moved there and I was only four–what did I know about what the earth could give if you just put a little effort?

All I knew then was that I felt a strange, strong connection to that dirt, its scent, the way it made a space in me and stayed there, like it was touching on something ancient, that existed deep in me before I was even me. But this is the adult me speaking. The four year old Vanessa just felt the pull, the want to be lying on the earth, hair slick with mud, dirt pilled on my neck, underneath my fingernails.

I’ve smelled that same scent and felt that same pull many times over the years. This string, an umbilical cord, has never left me.

It was in that yard that I first heard the song of a bird I don’t remember ever seeing, but every day I heard it’s croon, so I started to imitate it through the gap in my teeth. Years later, I’d learn it was the song of a male red cardinal.

By mid-summer, we had a lush garden, and I’d learned how to climb the plum tree. The sunflowers grew so tall and heavy, ma tied them to the fence to keep them upright. We ate from the bounty of that yard every day—diced tomato and cucumber salad, meat dripping with sofrito made with ma’s onions, peppers, cilantro and recao. It was from my perch on a branch that I watched her joy when she first saw evidence of baby tomatoes and eggplants.

I picked a still green plum from a nearby branch, bit into it and let the bitterness burn my tongue.

I was in my forties and a mother myself when ma revealed how she learned to garden. Up until then, her stories of her childhood in Honduras were of hunger and suffering.

Her face grew wistful and nostalgic, the way it did when she spoke of Abuelita Tinita, her grandmother who raised her. “Ella fue mi madre,” ma often said. They lived in the campo, in Sabá, Honduras, where Tinita taught her to toil the earth, growing enough to eat and sell. Ma laughed when she talked about abuelita’s stubborn mule. Whenever he was tired, he sat and refused to move no matter how Tinita slapped his ass to get him moving. Once, he sat in the middle of the river they were crossing. Abuelita had to unload the goods he was carrying, and they sat at the river’s edge for hours until the donkey decided to move again.

Ma’s eyes welled and she blinked hard a few times. “Ahí tuvimos de comer.” In the city the land was scarce, so Abuelita couldn’t plant enough to feed them. “Ahí sufrimos,” ma said, “pasamos hambre.” When I asked why they moved to the city, she shrugged. That’s where her mother and the work was.

“In some native languages the term for plants translates to ‘those who care for us.’” When I saw this Robin Wall Kimmerer quote making its rounds on social media, I thought of my mother’s writing about her travels to Sabá, on train and on foot with abuelita, where they had to walk miles through the banana plantation fields owned by the US owned Standard Fruit Company. I’d learned in college that Honduras was the first banana republic, but ma’s was the first personal story I read about those plantations.

She described in incredible detail how she studied everything with the intense curiosity of a child. I imagine her eyes twinkling speckled amber like my daughter’s do in the sun. They grew wide as she takes in the huge banana leaves that looked glossy, almost white with the morning dew; the varying sizes of the banana clusters on trees that were uniform in size; that tree that marked the end of the groves and beginning of the hardest part of the journey, where the shade and cool of the banana trees were gone. If it rained, they had to trudge through bogs of mud, but before they went on, Abuelita sat ma at the foot of “un arbol de jobo” to eat the lunch she’d prepared before the sun came up and they set off on their miles-long trek–tortillas, frijoles and scrambled eggs with a cup of black coffee. Ma recalled that ritual of sitting at the foot of that tree so many times before continuing on, crossing rivers, streams and various villages until they reached that town where they learned about how the earth takes care of us.

I was stunned to learn that the “arbol alto de jobo” in English is called a hog plum or june plum tree. I know now this too is how the earth takes care of us–as girls we both had a plum tree that marked our journeys.

Our second summer in that apartment, I started climbing into the junkyard next door when ma wasn’t looking. It was piled high with rubble, old tires, license plates with sharp, curled edges, lumber with rusted nails jutting out, an occasional needle, cables, wires, rats, feral cats, rubble. Shrubs and trees pushed up through all that trash, and at the height of the summer, the foliage grew so thick that when I looked at the right angle, I could almost forget where I was. It was a jungle to my five-year-old eyes. The mounds were ancient structures built into the ground. Somehow the dark magic within had been unleashed, and I was called there, the female Indiana Jones, to save the world from its wrath.

It was in that garden and that junkyard that I became fascinated with the earth’s fauna and flora; all things green and squirmy. There began my fascination with trees.

It was up in that plum tree that I became a writer when I started telling myself stories of a life where my mother treated me with the same tenderness with which she treated her plants.

Once, ma sent me out to gather tomatoes and peppers. “Para’l sofrito,” she said. Small piles of onion and garlic lay on the cutting board on the table. The day before I’d noticed that the tomatoes were red and green. I turned them over like I’d seen her do, careful not to snap them from their stem. They were firm to the touch.

When I climbed out into the yard, I gasped at the scene that greeted me. The rats from the junkyard next door had feasted on her vegetables. Peppers, tomatoes and eggplant lay scattered about, bitten into in chunks. I could make out their tiny teeth marks on the flesh. A few hung limply on the bush. The rats had even bitten the flower heads off their stems. I gathered what I could and climbed back into the apartment.

“Mommy,” I said in almost a whisper. “The rats ate them. These are the only ones left.”

Ma slammed down the knife she was using to chop the cilantro and stomped out to the yard, where she cursed “¡Estas malditas ratas, coño!” and yanked up some of the bushes. I ran to hide in my room, and didn’t come out until she called me for dinner.

Ma eventually brought her plants inside. “Here I can protect them,” she said. She perched them at the top of cabinets and bookshelves, on the window gates, hanging from hooks in the ceiling. She had so many on the table in her living room that her table for four could only seat one. And her light bill was always astronomically high–Con Edison made bank off my mother! $300 a month for a tiny railroad style apartment because of the lights she kept on 24/7 for her plants. “Son mis hijos,” she said.

The backyard went back to the condition it was in when we first moved in.

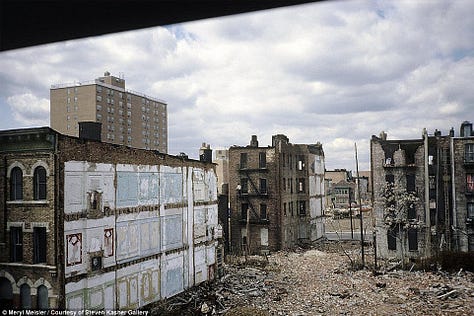

Sadly, I don’t have pictures of ma’s garden, but I have images of the neighborhood that surrounded it.

I remember watching the news on our small TV with its makeshift antenna made out of a wire hanger. The images of Beirut after the bombings in the early 80s reminded me of home.

A once thriving neighborhood, Bushwick was left looking like a war zone as a result of what some have called “the Fire War” where between 1965 and 1980, there were over a million fires in NYC. The South Bronx is most infamous for the aftermath, but Bushwick was just as devastated. The neighborhood was left dotted with trash and rubble strewn lots, abandoned and burnt out buildings that became crack houses in the crack era that ravaged the city starting in 1985.

My mother built a garden oasis in that war zone. I’ve carried it with me ever since.

When I became a mother, I shared my love and respect for nature with my daughter, taking her to parks around the city and hiking their trails. We’d take hours-long train rides to the beaches, Rockaway, Brighton, Coney Island. This was how I introduced her to the idea of a higher power when she was in Pre-K. Ma always sneered at my belief system, so different from hers, but if I believe in anything, I believe in nature, and that started in ma’s garden oasis.

“God is in everything, mamita,” I said to little V, “In the trees, the clouds, the birds. God is in you.” She started interrogating this on our commutes to school. She’d point at a flower, a lamp post, a traffic light and ask: “Is God in that flower? Is God in that lamp? Is God in that light?” Once, a man walked by with his dog. When the dog stopped to do its business, little V giggled and looked up at me, her supernova smile taking over her entire face. “Mommy, is God in poop?” I laughed with her. “Sure, God is in poop, too.”

Wherever I’ve traveled or moved to, I’ve searched out woods–the redwood forests of Berkeley and Oakland; a tree lined trail in Decatur, Georgia; the deep woods of Portland; El Yunque in Puerto Rico; the pristine pine forests of the San Jacinto Mountains of Southern California. At home in NYC, it was the old-growth forest of Inwood Hill Park that saved me when my brother, my Superman, Juan Carlos, died in 2013. I’d been walking that forest for years, but it was in my grief that I really started hiking its trails in earnest. I found paths created centuries ago by the Lenape, some so steep you have to grapple up. I discovered their ancient healing circles that are now being maintained by Tainos.

One day that summer, I went into the forest, a mantra in my head: “I need you to hold me. I need you to hold me.” My face was streaked with tears, snot dripped out of my nose.

It started in front of me, blue jays chirping so loud, I had to stop. Sparrows to my right. Red cardinals to my left. Titmice and nuthatches behind me. The birds carried my broken heart into their throats.

I was being held in bird song.

In healthy forests, each tree is connected to others via a fascinating microscopic network of fungus also known as mycelium or the wood wide web. It’s through this network that mother trees, the oldest, largest and most connected trees, are able to share life-supporting nutrients like water, nitrogen, carbon and other minerals with saplings growing under the canopy, where there often isn't enough sunlight reaching their leaves to perform adequate photosynthesis.

Their survival often depends on mother trees.

When my wife and I moved in together in 2016, it was the deck overlooking the park that sold the Bronx apartment. For years, I’d dreamed of living somewhere that looked out onto a forest. I’d imagined plants hanging on windows, and a backyard garden like the one ma had, but I hadn’t inherited ma’s green thumb. The only plant I hadn’t killed was a Golden Pothos, also known as Devil’s Ivy because it’s nearly indestructible. I named her “La Doña,” and gave friends cuttings when they visited.

Over the years, I expanded my vision and my construction worker wife helped bring it to reality. She hung lights, put up hooks, installed shelves and planters.

When the pandemic hit, I set my eyes to the deck. If we couldn’t go anywhere, I would create a space where we could relax and remember hope. I recruited my little family—little V and K— and together we started germinating seeds, and I started buying plants and flowers from the many vendors that sprouted up around the hood.

I called ma to ask for advice. Our relationship was tenuous, as always, but she answered, giving me specific instructions on how to grow and harvest green beans. She even bought me a hydrangea, telling me it was one of Abuelita’s favorite flowers.

I thought I’d finally found something to connect us.

By mid-summer, I had so many plants on my deck, there was barely enough room for people. They were stacked on the ground and shelves, hung on hooks, piled onto the table.

Every morning, I’d open the door with a smile, my café con leche in hand. I even sang to my plants, as I greeted each one: the hydrangea in the corner, the hibiscus, the various coleus plants whose leaves grew to the size of my head. The first vegetable I planted were green beans, as ma suggested. I squealed when I first saw a pod emerge and I thought of ma in her garden all those years ago, the immense joy that overtook her face when she first saw evidence of vegetables on a vine. By mid-summer, I had so many plants perched everywhere that there was barely enough room for humans.

It didn’t take long for me to see that I’d created an oasis on my deck like ma had done in her garden during my childhood.

Throughout the world and throughout history, where there is war and hardship, there are gardens. Built by individuals and communities, on rooftops, school grounds, windowsills, decks, fire escapes. Directly in the earth, in barrels, pots, repurposed milk jugs.

Wherever and whenever they can, humans find a way to grow vegetables, fruit and flowers. In refugee camps populated by thousands fleeing violence and brutality, gardens dot the landscape, even in arid, desert climates like Jordan. During WWI, the war most associated with trench warfare, there is photo evidence of flower and vegetable gardens grown in those trenches. Victory gardens surged in the US during both world wars so by the end of the second, they were providing more than 40% of all the vegetables grown in the US.

Victory gardening saw a dramatic resurgence during the pandemic, as witnessed all over social media where people shared how they were growing food in whatever spaces they could—rooftops, fire escapes, empty lots, backyards. I was one of those people.

It was on that deck that Katia and I started planning for our future. When we talked about marriage, we agreed not to put all our money into a ring or a wedding. We wanted a house and we wanted land. In the fall of 2020, when we came to see the house in the Hudson Valley that would become our home, we walked the 6.5 acres of land for 45 minutes before we even stepped into the house. Just feet from the patio stood a fenced area that had once been a garden created by a past owner. There were gaping holes in the fencing, and it was laden with fallen branches and a huge mound of ash and charcoal from the wood burning stove. I saw the potential immediately. I thought of ma and her garden.

I decided quickly that I was going to follow indigenous agricultural practices that say you don’t plant on land you’re new to for an entire growing season. I was there to be a steward; to let the land teach me and learn from its gifts. Ma didn’t get it. Said, “Ay, tu si tienes unas cosas, Vanessa.”

But the land affirmed my decision. One of the first things that came up was bleeding hearts. When Carlos died, I went to Flower Power in Alphabet City and bought us bleeding heart tinctures because I’d read that they help with grief. I discovered peony bushes on the side of the house and along the circular driveway. Peonies were my bridal flower, but ma wouldn’t have known that because she didn’t come to our wedding. She didn’t approve of me marrying a woman despite raising me with her partner, a woman, my second mom Millie, whom she was with from the time I was three in April of 1979 until Millie died in 2005. Ma nursed Millie while she was dying of cancer, and when she finally died, Ma went back to being a Jehovah’s Witness.

“Les di un mal ejemplo,” she said.

The second spring on the land, I spent days clearing out the 25 x 30 foot garden while Katia repaired the holes in the fencing and added panels. There’s an old, sacred energy about the space. I can feel the care that was put into it in the details, like the stones that line the perimeter to keep out burrowing animals like rabbits. The person who built it had a deep connection to the earth: a hydrangea bush marks due north and the entrance to the garden is due south, a lilac bush marks west, and an enormous fir tree is due east.

As I tilled the land, I imagined sending my daughter out to get me ingredients for my sofrito—onions, scallions, ajicitos, garlic, cilantro, recao, a bit of celery if my taste buds ask for it. I imagined her cutting a fat tomato, like my sister did when we were kids, sprinkling some salt on it and taking a big bite, the juice dripping down her chin. Eyes closed in utter delight.

The first time ma came to our land the summer after we moved in, she asked me to give her a tour. Her face lit up like a kid. She giggled as she climbed the tree house, pulled stems and leaves from the ground, showed them to me, saying they looked like some weed or plant from Honduras.

Then a cruelty surfaced that startled me. She threw rocks and sticks at the frogs in the pond, shared memories of her childhood when she squeezed the frogs until they burst, secreting a white liquid. When I winced, she said: “Dios hizo el mundo para los humanos.” I shook my head. I still don’t believe that god made the earth just for humans. In fact, I think that’s why we’re now dealing with the horrors of climate change—because we’ve been treating the world like colonizers instead of living in unity with it.

Ma scoffed when I said, “God made the earth for us and all its creatures, ma.”

The second and last time she came was to see my garden. It was late spring so the green was just starting to push out of the soil. I’d invited her so many times, sent her pictures, called to ask for advice. Eventually her sister, my querida Titi, convinced her.

I was so excited to show her what I’d done and how she’d inspired me. She started criticizing immediately. “Didn't I tell you…” She only stopped because Titi shushed her.

When she sat down, I turned to go into the house to get us some refreshments. Then I heard her say: “Y quien vive asi?” Who lives like this… She said it almost under your breath, just above a whisper. When I turned to look at her, she raised her brow, shrugged her shoulders and looked away. We left a little while later.

I got my first flat tire that day, and thus began six months of car issues, which was torture because living in the countryside, I need a car to get anywhere and everywhere. I didn’t blame my mother then nor do I now. I see this now as evidence that she too was a powerful bruja, even if she didn’t claim or embrace her powers.

That night, I cried into Katia’s arms. She asked, “What were you looking for, baby? Approval?”

I shook my head. “Connection. I was looking for connection.”

That day I learned that not even this, our love for putting our hands in the soil, could connect us.

When ma died, it had been 364 days since I went no contact. I was 46. It wasn’t the first time we were estranged. We’ve had periods like this, months and months of silence. This last time wasn’t the longest. This was the nature of our relationship for decades. Until that day on June 4th of 2022, when at 46, I finally said no.

We were at a family event in Titis’ house. As soon as I walked in, I knew she was off. That’s the only word I have to describe my mother’s unpredictable moods. When she cut her eyes at me, I felt air freeze up around me. I imagine a scene in the movie The Day After Tomorrow where you watch everything freeze up swiftly, inch by inch, so by the end of it, the entire city of NY is frozen solid. That’s what it felt like for me when ma was in one of these moods. My entire world froze up. She was curt. Gave me an icy “hi” as I leaned in to kiss her. She didn’t kiss me back. I avoided her from that moment. It didn’t take long for things to get even more tense. I did something she didn’t agree with. At one point she said: “¿Y quien eres tu?” I stared at her, exasperated. How far would she take it? I never knew. It didn’t matter who or how many people were around. Once she revved up, there was no stopping her.

My mind goes to a memory of when I was nine or ten. We went up Myrtle Avenue to Fabco to get me a pair of shoes. Me and these fat feet, my heavy step, my shoes never lasted long. It’s still that way in adulthood. I’ve learned to pay more for my shoes so they last me. Thicker soles, thicker leather, well made shoes, made to last. Fabco shoes weren’t that, but we were poor. Ma got me what we could afford.

I was excited to be with her. Just her and I. Those moments were so rare.

On our way back, we stopped at the Italian ice kiosk outside the pizzeria. This too was a rare treat. “Can I get a large,” I asked, peering up at her with begging eyes. She nodded, a small smile on her lips. “Dame un large, plis,” she said to the young scooper. I ordered the cherry flavor. We’d walked a few blocks when ma stopped suddenly, stared at me, the rage already dripping from her lips, “¿Dónde están los zapatos?”

My eyes grew wide. I felt the ice drip onto my hand and down my arm. I stared down at my other hand where the bag of shoes should have been but wasn’t. That was when she gave me the first slap across the head.

She berated me the entire walk back to the kiosk. Retardada. Ordinaria. A ti no se te puede comprar nada. No sabes cuidar las cosas. Estupida. Dejas la inteligencia en la escuela.

The Fabco bag was leaning against the wall next to the salesman. He handed it to us with a smile. “She was so excited about that Italian ice.” When ma snatched it and pushed it at me, the young man gasped but said nothing.

She beat me for blocks. When I threw the unfinished ice into a trash can, she slapped me again. Called me ungrateful. Just then, a man in a passing car stuck his head out of the window and yelled, “Stop hitting her, abusadora.” She turned to me, face filled with disgust. I backed into a corner and balled myself as best I could. I already knew what was coming: her and her open palm, slapping, coming down on me hard. And the names that slapped me harder than her hand ever could: Ordinaria. Estupida. Retardada.

This was my fault. I’d lost the shoes ma bought me. We didn’t have money like that. I was ungrateful. I was messy. I lost everything. I deserved to be beaten and berated.

She gave me that same look of hatred that last time I saw her. But this time I had decades of healing under my belt. That’s how long it had taken me to undo the damage, to believe myself worthy of more, of better. To know that this wasn’t my fault.

I came out of the door into the backyard to see ma glaring at me, eyes pinched, lips curled, face twisted with so much hatred and disdain. I said, “No. Don’t look at me like that.”

“Vanessa, respect me, Vanessa.” she said, over and over. I walked away. It was the last words we exchanged.

Seeds first grow down, away from the light and into the soil. They must do this to establish their root systems, in order to thrive. Once they are stabilized, they can grow up, breaking through the soil towards the light of the sun.

When I learned this, I thought of the shadow work I’ve been doing now for years, quiet and alone, it’s the hardest work I’ve ever done. No one sees how hard I had to fight to push through out of that darkness. They only see me now, all branches, blossoms and leaves, saying no, saying stop, knowing I deserve more, better.

Ma died on June 3rd, 2023. I had planned to finally plant seeds in my garden—cucumber, snap peas, string beans, zucchini, corn for my three sister’s patch. I’d been preparing for weeks, tilling and testing the soil, shoveling layers of compost in swaths. I handled the seeds tenderly like I’d watched ma do all those years ago from my perch in the plum tree.

I went into the garden three days later. I did as I saw ma do—poked my finger into the ground to make a shallow hole where I dropped a seed, then covered it loosely with dirt. I wasn’t there long, on all fours, when a red cardinal started making a ruckus. I looked up and there he was, staring at me from a low branch on the fir, chirping the same song I heard first in ma’s garden oasis four decades ago. “Hi ma,” I said. Tears rained into the soil. I looked at my hands, turned them over, dirt caked deep in the creases and under my fingernails.

Ma once told me I abandoned her when I left her house at thirteen. “I thought you were gonna come back,” ma said. I didn’t, but I’ve carried her everywhere I’ve gone…sometimes to my detriment.

There’s an oak tree on our land that doesn’t shed its dead leaves from the previous fall until spring. Scientists speculate that trees do this to continue to feed themselves from the dead leaves throughout the cold months, sucking the nutrients that remain.

Even in nature there are living things that hold on to dead, decaying pieces of themselves, to feed them through the harsh winter of healing. In the spring they can be shed for new life to be born.

It was my ma who instilled in me a love for nature, flowers in the spring, vegetables harvested mid and late summer, in that garden oasis and our trips to Forest Park, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, peach orchards in Long Island, and the city’s beaches.

I have a different perspective now on those six months I was without a car after my mother’s first visit to my garden: I think the land was keeping me close so it could help me heal. I spent that time becoming one with it and have been doing this since, getting to know the creatures who inhabited it long before I arrived, listening, observing, learning, respecting.

When the temperature dipped, I put bird feeders on our deck and spent hours watching the cardinals, nuthatches, finches, juncos, blue jays, sparrows, three different kinds of woodpeckers.

I learned to mark the beginning of spring by the frog orgy in the pond whose raucous chatter echoes through the forest for weeks starting mid-March. I've gotten to know the many surrounding trees—the spruce by our bedroom window, the cedar just outside the front door, the aging fir trees in the roundabout, the many red maples and junipers, the crab apple and the single pear tree who gave fruit only once since we’ve been here.

I’ve planted pieces of us too—morning glories in the garden and on the deck because they bring me back to that backyard on Palmetto Street where they climbed the fence and curled around our clothesline; a magnolia I dubbed Magdalena for thirteen year old Vanessa who fell in love with them that first spring I was away at boarding school, when I didn’t yet know that I’d left that backyard for good; a weeping willow by the pond for my beloved brother and his son Justin; the north section of my garden, where a hydrangea tree grows heavy with large, showy flower clusters in early-summer, is an altar to the divine feminine, for Abuelita Tinita who loved hydrangeas, and for my mother, me and all things mother wound healing.

Being with the land has also meant witnessing the circle of life, in all its shock and wonder. Once, a katydid got in the house and kept me up with its high pitched, staccato song. When I found it the following morning nestled in one of my plants, I released it with a giggle and a “good luck, little bug.” I gasped when a red cardinal swooped in and made a meal of it mid-air.

Last spring we had to meticulously remove a thorny vine that had taken over the hibiscus bushes out front. Those thorns hooked themselves into the flesh of my hands, calf, arm, back, breaking off & splintering into my skin so I had to dig them out with tweezers. It took hours but the bushes are now clear of vine, and a bit scarred and bruised, like me.

I discovered an Eastern phoebe nest under our deck and witnessed the entire life cycle from egg to hatchling. The mama and papa bird fluttered around and chirped nervously when I checked on the nest every few days. I teared up when I watched the hatchlings fly from the nest, and saw the process begin again days later when mama phoebe laid another three eggs. When a predator got to the eggs and knocked the nest down, a week hadn’t passed before they started building another one, in the exact same spot. I thought: Is this not what hope looks like?

Every time there’s a rainbow, I think of the biblical story ma told me that rainbows were a symbol of God’s promise that the world would never be drowned again. A ritual of desahogo, of undrowning, is what I do every day, with every word I write about us and every seed I plant in our name.

When the world feels heavy and I feel ready to crumble under its weight, it’s to the land I run to, my garden and the old growth forests that surround us. As a novice gardener, I understand my mother on a more profound level. I see why she created that garden in that war zone that was Bushwick, why she nurtured it for so many years, and how even when she abandoned it, she brought her plants inside to be closer to her. Putting my hands in the soil, I’ve discovered another way the earth can care for me—giving life to the seeds I plant, which in turn give me life through their wonder, color and nutrients. I squeal like a giddy child when that first sprout pushes through the soil, and when the zucchini starts to flower and produce fruit, the pain I carry takes on a different shape. If only for a little while, it’s not an anvil on my back or a boulder on my chest. It’s that seed burrowing down into the darkness to establish roots before it can push itself up towards the light of the sun. It is the promise of something beautiful.

In that garden oasis, my mother introduced me to a mother who would love me when she herself couldn’t. I wonder now if my mother knew that she was teaching me how to survive her.

©Vanessa Martir 2025

Thank you so much for this 🥹 I love your voice, & the imagery- I could see, smell, touch, & feel every moment! & the amount of crying I did while reading this- you have done a lot of work in your inner emotional garden as well, & it comes through so strong. And I want to say that even though I do not know you (yet)- I feel compelled to say that I am so proud of you. The amount of love & nuance you articulate here is one that has been nurtured & watered dutifully, and I can feel the pruning & awareness that you applied through each revision & the layers of emotional processing you did in your inner emotional garden (even though this piece does not show the process work- the intentionality & artistry echoes to create such an unconditionally loving piece that embodies all the seasons you have weathered within.) I cannot wait for your whole book if this is but an excerpt. Muchas gracias again for sharing your (& your mother’s) story & I look forward to reading & seeing more from you!

This is lovely. Thank you for sharing your story. My Mom, too, used to garden. I've never been even vaguely tempted, despite loving the same vegetables she used to grow. All I can think is that there'll be bugs. And there's little I can imagine more terrifying than having an insect crawl on me.

I lived & taught in Jesus de Otoro, Honduras for a year. One of the best years of my life.