Writing the ghosts that haunt

Excerpt of a craft talk on why I write about trauma, & how this work has helped me find (& continuously recreate) my freedom

I gave a craft talk this week on writing about trauma titled “Writing the Ghosts that Haunt”:

We all have them: stories of our lives that haunt us, that we’ve written about in our journals or masked as someone else’s story in fiction or and/or tried to write about it in personal essay or memoir. Perhaps you’ve grappled with how to tell it, whether you should tell it, if anyone will care if you tell it. Maybe someone’s told you no, you shouldn’t write that, it’s shameful, something to be tucked away somewhere deep and dark, for no one to see.

As writers many of us feel inclined to excavate these stories in our work. Some of us can’t avoid it, but why? How do we gather the audacity? How do we dare?

In this craft talk, I’ll discuss how I came to write the stories that haunt me, the writers I’ve turned to for inspiration and courage, and why I continue to do this work of examining and interrogating my trauma; what I’ve learned on the journey, why I feel this has been my ultimate redemption, and why writing about your monsters can be yours.

I decided to share a portion of the talk here. (Not the whole thing because, hello, why would orgs bother to commission me if I share all of it here?)

I started the talk with an excerpt from the essay, “Dreaming a Sacred Garden”, that was recently published in Aster(ix), which is also a reworked excerpt from my memoir, and went on from there…

I begin my memoir, A Dim Capacity for Wings, in my mother’s garden. We moved into that first floor apartment on Palmetto Street in Bushwick, Brooklyn in the spring of 1980, the same year Reagan was elected, Sugar Hill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight brought a new music genre to the national stage, and a fierce heatwave hit NY, making August the hottest on record. I was just four years old, but I remember watching my mother standing by the window in the morning, surveying the backyard, her coffee in hand, the steam fogging the glass. Piles of trash littered the yard, and the makeshift barriers that separated ours from the surrounding yards, were made of plywood clumsily nailed together and falling apart, so there were gaping holes in spots.

Days later, mom climbed out the window and went to work. She swept up the years of garbage, bags that smelled of something dead or dying, cracked flower pots, a fork with twisted tongs; and threw it all over the dilapidated fence into the junk yard next door. She wasn’t littering. That yard was piled high with trash already. It was one of the many rubble strewn lots that dotted our neighborhood.

Between 1965 and 1980, there were over a million fires in New York City. The time is referred to as Fire Wars, and the South Bronx is most notorious for the aftermath. According to census data, the Bronx lost more than 90% of its buildings to fire and abandonment between 1970 and 1980. The era is chronicled in the Netflix Show The Get Down and the PBS documentary Decade of Fire. Bushwick, Brooklyn isn’t part of the story of the Fire Years, but it was just as devastated.

I remember seeing images of Beirut after the bombings, and thinking: “That looks like home.”

The Bushwick I grew up in was dotted with rubble and trash strewn lots and abandoned, burnt out buildings that became crack houses in the crack era that decimated our neighborhoods in the 80s and 90s.

My mother created a garden oasis in that war zone. And I became a writer in the plum tree of that backyard.

My mother wasn’t a Martha Stewart type of gardener with a sun hat and apron. She worked in a sofrito stained nightgown or a t-shirt and shorts. She took to tilling the soil, using her right leg to push the old shovel into the ground to bring up the dark soil with squirming earthworms. When the earth wouldn’t give, she got on all fours and used her hands. Then she went out and bought the seeds. Each packet had a picture of the potential inside: peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, squash, herbs like peppermint, cilantro and rosemary, flowers like geraniums and sunflowers. She handled the seeds with a tenderness I envied.

Those seeds, plants, flowers and bushes got a quiet, consistent care and tenderness from my mother that she seemed incapable of giving me. This is how I introduce the reader to what the heart of my book is about: my relationship with my mother, this wound that has shaped the course of my life.

Processing pain in private is a difficult task. Writing stories that reveal the growth and gaps that stem from trauma is even more challenging, especially when we do it for an audience, and especially when you’re a woman, a queer woman, a woman of color. It’s only now, having left my mother’s house 33 years ago this fall, now myself a mother (I have a daughter in college) and an out and proud queer woman with a wife, that I can reckon with the truth of what happened to me.

In her essay, “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” Leslie Jamison wonders: “How do we talk about these wounds without glamorizing them? Without corroborating an old mythos that turns female trauma into celestial constellations worth of worship?”

I answer these questions through craft. I circle the site of trauma throughout my essays and my memoir, in an effort to illuminate new complicated truths at each turn…

But the stories we most need to tell, the ghosts that haunt us, don’t have beginnings, ends, or morals, unless we write them that way. And that’s why I wrote fiction for a long time before I ventured into the world of autobiographical writing. To me, as a fiction writer, narrative has a purpose: it’s how I create meaning. When I tried to tell the stories of my trauma, it devolved into a painful litany of “and then.”

My mother couldn’t mother. And then I was molested. And then I didn’t tell my mother. She was abusive. I didn’t feel safe. And then I internalized all of it, believing that if I did this or that, she would love me. And then she didn’t. And then I left at 13, and never moved back.

And that was it. I got lucky. I got out.

In the essay, “How Writing Fiction Helps Me Give Shape to the Chaos of Trauma,” Rahna Reiko Rizzuto writes: “Trauma is a loop. It is disorder, by definition: a break in understanding and time. The narrative stalls; it goes nowhere, repeats, leaving you stuck in feelings and fragments that can be too hard to bear. I have found this trauma loop in much of my research for each of my three books, including most recent, among the survivors of Hiroshima, who lived through something so far beyond nightmare that the only way to pull themselves out of it was to create a narrative to make sense of the senseless, or to block it, as much as possible, from their minds.”

Trauma is often remembered in fragments. The consensus among psychiatrists is that these memories aren't usually put together properly. Instead, they include intense emotions, sensations, and perceptions. Memories of traumatic events can eventually be constructed into a narrative but usually remain fragmented. These fragments are the ghosts that haunted (still haunt) me: the garden, my struggle to make my mother love me, the abuse I endured at the hands of a neighbor, then an ex-boyfriend and onward. I struggled to shape them into a narrative that I could make meaning out of. They still found their way in through my obsessions, and what I wrote about in my fiction: abusive relationships, antagonistic mother-daughter relationships, women who fought to free themselves and finally did, after much struggle and suffering.

Let it be known: it takes incredible courage to stand alone in the spotlight of your own stories and try to make sense of them. (Let me confess: logically I know this to be true, but emotionally I don’t always feel courageous when I’m doing this work. More often than not, I don't feel courageous at all.) The central question asked in memoir is: How did this happen and what do I or did I do about it? Answering these questions requires a kind of healing and recovery that I had not yet found, so I sought it out and tried to make sense of it all in fiction.

My memoir is a collection of essays. I chose this structure because it enables me to revisit and relive the trauma the same way I experienced it. Yes, there are obviously things about trauma that remain fixed, like the image of my mother in her garden and me in the plum tree longing for her remains consistent. That’s why the first essay in the book, “In Search of My Mother’s Garden”, begins there. But in order to understand what happened and why has required that I go through different stages, and for me, the best way to chronicle that, is through essays that are interconnected.

My imagination gave me a framework to process the emotions that roiled inside of me—grief, terror and their consequences—and allowed me to enter my own traumatic experiences sideways and linger inside them. I gave them to characters whose struggles mirrored mine. They were lucky enough to find antidotes (even when I myself hadn’t or couldn’t): like love, connections, community, family. In other words, I was able to enter–and exit–the trauma loop through stories I created that weren’t exactly the same as mine, but I could see myself in.

For a long time, I used to say that I ran away from memoir by writing fiction. I don’t believe that anymore. I think if anything, my fiction writing helped lead me to my heart, to the stories I really wanted to write, to my essays and memoir.

My memoir is a collection of essays. I chose this structure because it enables me to revisit and relive the trauma the same way I experienced it and re-experienced it long after I’d left my mother’s house at 13 to make my way in the world.

Yes, there are obviously things about trauma that remain fixed. The image of my mother in her garden and me in the plum tree longing for her remains consistent. That’s why the first essay in the book, In Search of My Mother’s Garden, begins there. But in order to understand what happened and why has required that I go through different stages, and for me, the best way to chronicle that, is through essays that are interconnected. Sarah Kasbeer, author of “A Woman, A Plan, An Outline of a Man” describes this as “triaging the thing that happened.” Only after do you begin to realize how experience affected you in different ways. For me, it was present in my relationships, both romantic and platonic, how I mothered myself, how I mothered my daughter, how I treated myself, the ways that I sabotaged myself and broke my own heart, my decades long relentless obsession with emotionally unavailable people—I’ve said that if there was an emotionally unavailable man within fifty miles of me, I was going to find him and I was going to make him love me. It took some time to realize that I’d also done this with woman friends. This trauma of being unmothered has seeped into every part of my life.

The memoir in essays as a structure has enabled me to look at my trauma through a prism that gives me a different lens on the same story. I can’t really write one essay about how I survived being unmothered, how it shaped me into the woman, mother, writer, sister, lover, wife I am today. There are other interconnected events: How did people respond to me? How did I manage (or didn’t manage) for years? What about other things that happened that I didn’t realize were connected? How did this trauma shape the way I responded (often inadequately) to other traumas? How did this trauma cause me to retraumatize myself? It’s a muddled cloud. Taking it essay by essay is helping me unmuddle that cloud.

In her essay The Grand Theory of Female Pain, Leslie Jamison writes:

We don't want to be wounds ("No, you're the wound!") but we should be allowed to have them, to speak about having them, to be something more than just another girl who has one. We should be able to do these things without failing the feminism of our mothers, and we should be able to represent women who hurt without walking backward into a voyeuristic rehashing of the old cultural models.

In The Empathy Exams, Jamison calls herself a “wound-dweller.” I’ve always liked that description. It’s in writing about my wounds that I’ve found my freedom, or rather, created it.

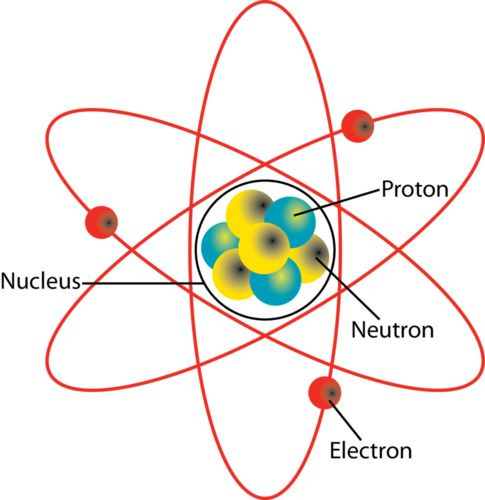

Being unmothered isn’t the only trauma I’ve experienced, but I’ve found that it is the primordial wound. I imagine it visually as a nucleus with protons and electrons circling it at varying speeds and distances.

The mother wound is the center, it’s the lens through which I view and navigate other traumas I explore and write about–being molested, sexually assaulted, enduring intimate partner abuse, my wildly abusive relationship with my sister, and more.

The protons and electrons circling the nuclear are the experiences I had after that were largely shaped by this wound. It fascinates me that so often whatever I write, brings me right back to that wound, to be unmothered.

I’ve asked myself the questions so many times times: Would have behaved this way if I wasn’t unmothered? Would things have gone down the same? How different would my life had been if I’d had a mother who could love me and treat me with tenderness and kindness?

So what happened that I finally wanted other people to know? What happened that I couldn’t run from the ghosts anymore? What made me decide to confront and write about my trauma? Why did I finally pick up a chair and (metaphorically) sit in all my grief and despair?

My brother, Juan Carlos Moncada died in June of 2013.

Carlos was, still is, my Superman. His kryptonite: heroin. He grappled with the addiction for fifteen years. In the last three months of his life, together we traced his unraveling to his discovering at 13 that he was conceived in a rape. I always think of Voldemort here. According to the story, Voldemort, the antagonist of the Harry Potter series, is incapable of love because he was conceived while his father was under a spell. He wasn’t conceived in love, thus he was incapable of love.

My dear brother, didn’t think he was worthy of love because he was conceived in a rape, and he was never able to overcome this wretched ghost that haunted him. That’s ultimately what took him out.

In her essay, Heroin/e, Cheryl Strayed writes: “It is perhaps the greatest misperception of the death of a loved one: that it will end there, that death itself will be the largest blow. No one told me that in the wake of that grief other grief’s would ensue.”

When my brother died, I reeled into the darkest place of my life. It was there that I was confronted, no confronted is too soft a word…it came at me with the strength of a thousand chupacabras, this trauma I’d been walking with and running away from for my whole life: My terribly antagonistic relationship with my mother. There was no running from it, so I did what I’ve always done, because I’m a nerd, and it’s what I do: I embarked on a years long, obsessive research project on strained mother-daughter relationships. In the journey, I found there is a name for women like me — unmothered — and there is a name for the pain I carry: the mother wound.

***

Here’s the thing: Writing about trauma, grief, sorrow, doesn’t protect me or save me when the trauma (re)surfaces and reminds that it still dwells in me, that my body keeps the score.

I’m currently enduring a bout of seasonal depression. It rears its ugly, opportunistic head at this time of year every year. The coming cold weather, the holiday season (my brother loved the holidays), the solitude and hibernation of the winter months, triggers an emotional response that always knocks me off my axis, even though it happens every year, like clockwork. I am never prepared.

Confronting my trauma in my stories, in therapy and other healing modalities, has helped me pay attention and advocate for myself when I need help. I spoke to my doctor this week about the depression. She upped my meds and reminded me of the various things I do to care for (mother) myself, cope and pull myself out it (or at least away from it) for a spell. Being in my body and doing physical work is one of those things. So yesterday, when I woke up with the ghosts spinning in my head, the sadness sitting on my chest was an elephant, and vulnerability hangover, I knew I had to take action: I had to get outside and I had to move. So I did just that. I walked our long driveway, and when I got back to the front of the house, I stared at the two piles of wood (cords) we’d had delivered. I resisted the voice that said: No, it’s too much. Let’s go to bed and binge watch Grey’s Anatomy (I recently started watching the series from the beginning for the nth time).

As Dr. Shepherd (aka McDreamy) said in an episode I watched recently: “Peace isn’t a permanent state. It exists in moments… fleeting. Gone before we even knew it was there. We can experience it at any time.. In a stranger’s act of kindness. A task that requires complete focus. Or simply the comfort of an old routine. Every day, we all experience these moments of peace. The trick is to know when they’re happening so that we can embrace them. Live in them. And finally… let them go.”

That’s what I did today when I piled all that wood into wheelbarrows and stacked it not so neatly in piles next to the house. There was something about the repetitive act, the focus it required, the movement of my body that helped me find/make peace. I stopped to giggle at the chipmunks, especially one who seemed particularly curious about what I was doing. I gawked, open-mouthed at the red-tailed hawks that soared above and screeched, as if to get my attention. (I’d heard them from my bed earlier in the day.) I listened to the symphony of nature for a while before turning on some music (Bad Bunny & Beyonce to the rescue) to keep me going when I got sluggish. It was a lot of work. Took me hours. But I found that elusive peace. My muscles ache. My back is stiff. I am stretching and feeling all of it. And, today, I am grateful for these tools, this wood, my body, these words…

This resonated. Every word. Thank you for sharing it.

I just wanted to say that I love your writing. It is so descriptive and imaginative. We grew up in different eras, but I, too, grew up in Ridgewood/Bushwick during the 60s/70s. I went to work in Manhattan in the era in which you describe, where everything was broken and ugly in NYC. It's been years since I've lived in NY, but it is a huge part of my life and I'll never lose those memories. We all have trauma to process. I have trauma that came after my time in Ridgewood, and I am trying to figure out the ways I can express myself about that. Again, great essay. Looking forward to more.